Higher prices. Slower growth. Farmers losing access to their biggest foreign market.

Even President Donald Trump is warning that Americans might have to accept "a little pain" before they enjoy the fruits of his escalating trade fight with China.

On the pain part, if not necessarily on the "little" part, most economists agree with the president: The tariffs the United States and China are preparing to slap on each other's goods would take an economic toll.

For now, optimists are clinging to tentative signals from the Trump administration that it may be prepared to negotiate with Beijing and avert a trade war.

But Wall Street is getting increasingly nervous. The Dow Jones industrial average lost 572 points Friday after being down as much as 767.

"There are no winners in trade wars," said Nathan Sheets, chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income. "There are only losers."

On Thursday, Trump ordered the U.S. trade representative to consider imposing tariffs on up to $100 billion worth of Chinese products. Those duties would come on top of the $50 billion in products the U.S. has already targeted in a dispute over Beijing's sharp-elbowed drive to supplant America's technological supremacy.

China has proposed tariffs of $50 billion on U.S. products that will squeeze apple growers in Washington, soybean farmers in Indiana and winemakers in California. And Beijing warned Friday that it will "counterattack with great strength" if the United States ups the ante.

Of course, it may not come to that.

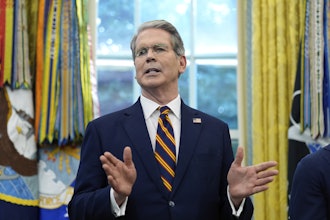

"We're absolutely willing to negotiate," Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said Friday on CNBC, adding, "I'm cautiously optimistic that we'll be able to work this out."

At the same time, Mnuchin warned, "There is the potential of a trade war."

Economists are already calculating the potential damage if talks collapse and give way to the biggest trade dispute since World War II.

The dueling tariffs could shave 0.3 percentage points off both U.S. and Chinese annual economic growth, according to estimates by Gregory Daco, head of U.S. economics for the research firm Oxford Economics.

In the United States, Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody's Analytics, said the dispute could wipe out half the economic benefits of the tax cut Trump signed into law with great fanfare in December.

"There's lots of different channels through which this hurts the economy," Zandi said. "The most obvious is, it raises import prices. If American consumers have to spend more on Chinese imports, they have less to spend on everything else."

In the first $50 billion in planned tariffs, the Trump administration was careful to limit the impact on American consumers, sticking mostly to industrial products such as robots and engine parts.

But if the administration tries to triple the tariffs, they will be more likely to hit the low-price Chinese products that American households have come to rely on, namely electronics, toys and clothing.

The administration appears to be betting that China will back down because it has more to lose. It sent $375 billion in goods to the U.S. last year, while the United States sent only $130 billion worth of products to China.

But China has other ways to retaliate. It could cancel aircraft orders from Boeing. It could meddle with U.S. supply chains by disrupting shipments from Chinese factories to American companies. Or it could raise U.S. interest rates by selling Treasury bonds or buying fewer of them.

The Chinese appear confident they can withstand more pain than Americans can. In a democracy like the U.S., "if people start to hurt, they're going to complain," said Sheets, who was undersecretary for international affairs in the Obama administration Treasury Department.

They're complaining already.

Zippy Duvall, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation lobbying group, warned that the dispute has "placed farmers and ranchers in a precarious position."

"We have bills to pay and debts we must settle, and cannot afford to lose any market, much less one as important as China," Duvall said.

Last year, the United States sold $12.4 billion in soybeans to China — nearly 60 percent of all U.S. soybean exports.

Trump, who received overwhelming support in rural America in the 2016 presidential election, has directed Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue "to implement a plan to protect our farmers and agricultural interests." But a move to support American farmers could widen the trade dispute.

"Farmers in countries like Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Canada and Europe would now find it difficult to compete with newly subsidized U.S. agriculture," said Chad Bown, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. "As a result, they might demand retaliation against U.S. exports or subsidies of their own."

___

AP Business Writer Marcy Gordon in Washington contributed to this report.