TOKYO (AP) -- The disaster in Japan has exposed a problem with how multinational companies do business: The system they use to keep supplies rolling in is lean and cost-effective -- yet vulnerable to sudden shocks.

Factories, ports, roads, railways and airports in northern Japan have been shut down or damaged because of the stricken nuclear plant in the region. So auto and technology companies are cut off from suppliers in the disaster zone. Some have had to stop or slow production.

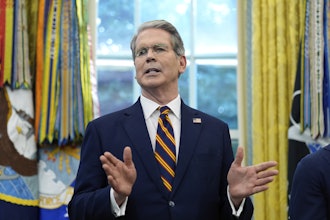

"When you're running incredibly lean and you're going global, you become very vulnerable to supply disruptions," says Stanley Fawcett, a professor of global supply chain management at Brigham Young University.

The risks are higher because so many companies keep they inventories low to save money. They can't sustain production for long without new supplies.

Subaru of America has suspended overtime at its only North American plant, in Lafayette, Indiana. Toyota Motor Corp. has canceled overtime and Saturday production at its 10 North American plants. The two companies are trying to conserve their existing supplies.

Among the auto plants damaged by the quake was one in Miyagi prefecture that supplies parts for hybrid batteries in Toyota Prius, Camry and Lexus hybrids. It's unclear when the plant, a joint venture of Toyota and Panasonic, will start running again.

Even companies whose Japanese suppliers escaped damage have scrambled to ensure supply lines remain intact. Ford, for example, relies on a Japanese plant for hybrid batteries for its Fusion, Escape and MKZ hybrid vehicles. That plant wasn't damaged in the quake. But Ford isn't taking any chances because of the transportation troubles in Japan. It's looking for alternate supplies and is looking into airlifting parts if shipping shuts down.

"The whole thing could change overnight," says spokesman Todd Nissen.

Automakers around the world have tried to copy the Japanese car manufacturing system, which is regarded as lean and cost-efficient. It's built around tight links between an automaker and its multiple suppliers. But if a kink develops in that system, known as the supply chain, an entire assembly line can shut down within hours.

Toyota says its vehicles contain 20,000 to 30,000 parts. Most come from about 600 suppliers. And the chain doesn't stop there. The 600 suppliers themselves rely on hundreds of other companies to provide raw materials and components.

Vehicles use lots of interchangeable parts -- from hoses and tubes to nuts and bolts. But thousands of other parts are custom-designed for specific vehicles. Steering wheels, seats, and even rear view mirrors can differ from car to car.

"You can't build a car if just 98 percent of the parts are available," says Fred Hubacker, executive director of auto restructuring firm Conway MacKenzie in Detroit. "Many of these parts are highly technical products that are not easily replicated."

The disaster is also threatening the supply of Japanese-made chips for consumer electronics, from washing machines to TVs to iPads. Factory shutdowns and crippled shipping routes pose a risk to companies that depend on chips for storing data. Japanese semiconductor giants Toshiba Corp. and Renesas Electronics Corp. have temporarily closed facilities because of the quake.

The electronics companies that depend on chips from Japan are trying to assess the depth of the supply disruptions. Chip prices have already jumped on fear of shortages. The price of a type of memory chip called NAND flash, commonly used in portable electronics, has surged more than 10 percent since the disaster, analysts say.

For consumer electronics, supply chains are complex. Some cell phones have dozens of chips. Apple Inc.'s iPad requires parts from around the world. The insides of the device show how much coordination Apple must have with suppliers around the world to ensure there are enough parts.

The Wi-Fi version of the iPad uses a Toshiba chip to help store data, according to analysis by iFixit.com. The chips that control communications come from Broadcom Corp., in Irvine, Calif. Memory comes from Samsung Electronics Co., in Korea. Texas Instruments Inc., in Dallas, makes a chip used for the touchscreen. The processor is designed by Apple, based in Cupertino, California.

Those are just the main semiconductor guts of the machine. A host of other chips, made by other companies, do other things in the iPad: powering the compass, for instance, and sensing when light hits the screen. All the other iPad parts, from the touchscreen glass to the screws and cameras, come from a variety of suppliers.

Toshiba was one of the companies forced to shut factories after the quake. So it's possible that the supply of chips for Apple could be disrupted and delay iPad shipments.

Apple has declined comment. A Toshiba representative did not immediately return a message from The Associated Press on Wednesday.

Hewlett-Packard's new CEO, Leo Apotheker, told the AP that his company's infrastructure in Japan is "more or less intact" but that it will take longer to figure out the extent of damage to its supplier network.

Market research firm IHS iSuppli estimates that Japan is the world's biggest supplier of silicon used to make semiconductor chips. Its supplies make up about 60 percent of the world's total.

Japan is also a key supplier of the "wafers" that are the building blocks of computer chips.

Barclays Capital analysts wrote in a note to investors that a shortage could squeeze big wafer consumers such as Intel, the world's biggest semiconductor company, and Texas Instruments.

Over the past two decades, multinational companies have built and tightly managed supply chains that span the globe. These chains link low-wage factories in places like China with operations in Europe, Japan and the United States. The emphasis, BYU's Fawcett says, is on being "lean and global."

Companies have kept inventories at a bare minimum to cut costs. Many have relied on what's called "just-in-time" management to quickly match supplies with sales.

But that increased efficiency has carried a risk: The lean, far-flung supply chains left multinationals vulnerable to supply shocks. And the shocks have come one after another.

The 2001 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington froze global transportation. The 2003 SARS outbreak shut down production in southern China. The eruption of a volcano last year in Iceland stopped air traffic over Europe. And now a disaster is unfolding in Japan.

Fawcett says companies are starting to rethink the wisdom of depending entirely on supply chains that must cross oceans. In the mid-2000s, he says, some U.S. companies started moving factories from China to Mexico. There, they could still take advantage of cheap labor without having to contend with ocean crossings.

He says he suspects the trend -- called "near-sourcing" -- will become more popular after the disaster in Japan.