Traditional incandescent light bulbs have been phased out throughout the world due to inefficiency. However, the old-school bulb could experience a rebirth thanks to a recent development.

Developed more than a century ago by Thomas Edison, the incandescent bulb provides a wide-range of light that brightens a room. That warm glow comes at a price though, as more than 95 percent of the energy put forth to light the bulb ends up being wasted. This wastefulness is what has led nations across the world to adopt more energy efficient alternatives, such as LED and CFL bulbs. Edison’s grand creation could make a comeback though, thanks to improvements planned by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technologyand Purdue University.

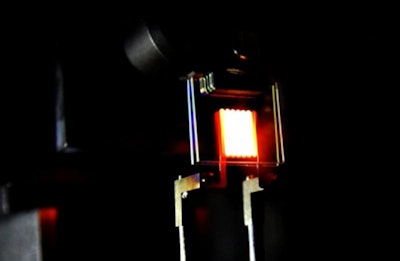

The improvement, which was reported in the journal of Nature Nanotechnology and touched on in a news release issued by MIT, stems from a two-pronged process. The first phase incorporates the wasteful heated metal filament found in traditional incandescent light bulbs. What makes the phase different is that it features structures surrounding the filament that capture the heat that is generally wasted as infrared radiation. Once caught, the radiation is redirected by the structures to the filament where it is re-purposed as visible light. The structures, which are a type of photonic crystal, are comprised of elements that are plentiful on Earth and can be created using material-deposition technology.

The crystal, according to MIT, “is made as a stack of thin layers, deposited on a substrate.” When these layers are constructed properly, one can receive a “very efficient tuning of how the material interacts with light.” With the new bulb, visible wavelengths leave the bulb, but are then reflected back as if they had been met with a mirror. After this, the wavelengths return to the filament, which creates heat that will be transformed into light.

The second phase makes the light bulb’s conversion of electricity into light more efficient, giving greater luminous efficient. The luminous efficiency of a light bulb factors in the human eye’s reaction to a light. The luminous efficiency of a traditional incandescent light bulb is between 2 and 3 percent. Those figures look extremely porous in comparison to CFLs, which have a luminous efficiency between 7 and 15 percent, and the most compressed LEDs, which hover between 5 and 15 percent luminous efficiency. The newly developed incandescent bulbs could have a luminous efficiency of up to 40 percent, according to the MIT and Purdue researchers.

The group’s first proof-of-concept units didn’t come near the desired efficiency mark, reaching about a 6.6 percent luminous efficiency. Despite coming well short of the ultimate efficiency goal, the group of workers said that the initial results already demonstrate a threefold improvement over modern incandescent bulbs.

“The results are quite impressive, demonstrating luminosity and power efficiencies that rival those of conventional sources including fluorescent and LED bulbs,” said Princeton University Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering, Alejandro Rodriguez, as quoted by MIT. Rodriguez, who was not a part of the work, added, “I believe that this work will reinvigorate and set the stage for further studies of incandescence emitters, paving the way for the future design of commercially scalable structures.”