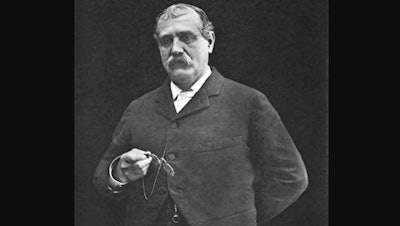

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (AP) — As the third president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Francis Amasa Walker helped usher the school into national prominence in the late 1800s.

But another part of his legacy has received renewed attention amid the nation's reckoning with racial justice: his role in shaping the nation’s hardline policies toward Native Americans as a former head of the U.S. office of Indian Affairs and author of “The Indian Question,” a treatise that justified forcibly removing tribes from their lands and confining them to remote reservations.

MIT is now grappling with calls from Native American students and others to strip Walker's name from a campus building that is central to student life — part of a broader push for the nation’s higher education institutions to atone for the role they played in the decimation of Native American tribes.

“Walker might be the face of Indian genocide and it is troubling that his name is memorialized at MIT,” says David Lowry, the school’s newly-appointed distinguished fellow in Native American studies and a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.

MIT President L. Rafael Reif wrote in a recent column in MIT Technology Review that addressing Walker’s legacy is an “essential step” in the school’s commitment to its Native American community. Native students account for 155 of the school’s nearly 3,700 students this year.

“The question we are working through now is what to do with these facts, as well as other aspects of the history of MIT and Native communities,” wrote Reif, who stopped short of weighing in on the name change debate in his column and declined to be interviewed.

Built in 1816, Walker Memorial houses student group offices, the college radio station and a campus pub. Its focal point is a great hall decorated with soaring murals meant to depict scientific learning and experimentation.

Alvin Harvey, a doctoral student and president of the MIT Native American Student Association, says the classical-style building overlooking the Charles River is one of the most visible reminders of the school’s white, Western-centric past.

“As a Native American individual, you feel the full brunt of what MIT built its foundations on,” said Harvey, a 25-year-old New Mexico native and member of Navajo Nation. “The ideology that Western men, white men are going to lead the United States and the world into a new utopia of technological development.”

MIT was among the nation's first colleges to benefit from the Morrill Act, a 1862 law that helped create the U.S. public higher education system. The law allowed for the transfer and sale of federal lands to colleges to help establish their campus, or bolster an existing one. But many millions of those acres were actually confiscated from Native American tribes.

In MIT's case, it received at least 366 acres scattered across California and a number of Midwest states, High Country News reported last year. At the time, their sales helped generate nearly $78,000, or more than $1.6 million in today’s dollars, the magazine said.

Lowry cautions those land and revenue estimates are likely conservative and that some students in his course on the “Indigenous History of MIT” are working on a fuller accounting.

Simson Garfinkel, an MIT alum who wrote a recent article on Walker’s life and legacy in MIT Technology Review, worries that renaming Walker Memorial would only serve to erase the contributions of a singular figure in MIT history.

“Without Walker there would be no MIT. He was pivotal to making it the institution it is today,” Garfinkel said. “He placed it on vastly better financial footing, dramatically expanded enrollment and brought a discipline to the school that was really needed.”

As president from 1881 until his death in 1897, the former Union Army general and Boston native helped improve student life and oversaw the introduction of the first female and Black students on campus.

Garfinkel also argued that “The Indian Question” offered significant and lasting contributions to the wider understanding of indigenous peoples, even if its analysis and policy recommendations were ultimately racist and “problematic.”

The book, published in 1874, included detailed descriptions of American tribes, their populations and the offenses incurred against them, mainly by white people illegally settling on their lands and instigating violence.

But Walker also described Native Americans as “an obstacle to the national progress” and concluded the country was justified in pushing Native Americans off their ancestral lands. He recommended confining them to reservations and forcing them to adopt European farming and production methods.

Rather than remove Walker’s name from the building, Garfinkel suggests providing more historical context by installing an informational marker on site.

“Walker was an amazing person who we need to understand in all of his complexity," he said. “It’s easy to rename buildings, but much harder to learn about the past."

Harvey said MIT has taken promising steps, such as appointing Lowry, recognizing Indigenous Peoples Day and providing a new campus space for Native American student groups.

But it still needs to hire more Native faculty and provide other support for Native students, he said. As for Walker Memorial, Harvey suggests not only renaming it, but turning it into a center for indigenous sciences.

“MIT is missing out on this huge swath of indigenous knowledge,” he said. “Indigenous people are practicing their own valuable sense of science, engineering and knowledge of the natural world, and it’s being completely shut out.”