WINCHESTER, Va. (AP) — In a normal year, hundreds of book lovers would have descended on Winchester this summer for Shenandoah University’s annual children’s literature conference.

Some would have made their way to Christine Patrick’s bookshop downtown. Winchester Brew Works would have rolled out kegs this month for Oktoberfest revelers. The Hideaway Café, occupying a prime location at the corner of Cork and Loudoun streets, would be advertising its monthly Divas Drag Show.

But 2020 is no normal year. The literature conference, Oktoberfest and drag shows have all been cancelled — casualties, like so much else, of COVID-19.

The pandemic has hammered small businesses across the United States — an alarming trend for an economy that's trying to rebound from the deepest, fastest recession in U.S. history. Normally, small employers are a vital source of hiring after a recession. They account for nearly half the economy’s output and an outsize portion of new jobs.

“Small businesses are the engine of the economy,’’ said Ahu Yildirmaz, co-head of the ADP Research Institute, a think tank affiliated with the payroll processor ADP. “In past recessions, they were the ones really fueling the economy.’’

Roughly one in five small businesses have closed, according to the data firm Womply. Restaurants, bars, beauty shops and other retailers that involve face-to-face contact have been hardest hit at a time when Americans are trying to keep distance from one another.

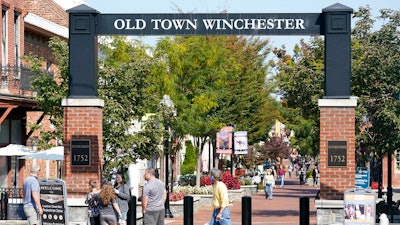

Small companies are struggling even here in a city of 28,000 that works hard to promote and preserve local enterprises. Founded in 1744 and fought over repeatedly during the Civil War, Winchester, 75 miles west of Washington, D.C., at the northern edge of the Shenandoah Valley, long ago blocked off several blocks to create a pedestrian mall downtown — a bulwark for local businesses that must compete against the big box stores on the outskirts of town.

To encourage foot traffic at local businesses, Winchester even designed traffic lights to make it easier to traverse downtown on foot than by car, sometimes to the consternation of motorists caught in stop-and-go traffic.

But city planning is no match for a global pandemic.

“We’re in such a weird, weird time,’’ said Mayor John David Smith Jr. “Small businesses and families are hurting.’’

Some Winchester businesses folded quietly in the spring, he said, choosing not to renew their leases. One was The German Table restaurant, which closed in April with this explanation on its Facebook page from its owner:

“I am always a happy and positive person, but I really think that this virus will be kicking a lot of small businesses in the ass!! With no positive changes in sight, reopening in maybe 4-6 months seems almost unrealistic.’’

Others are holding on. They're receiving government aid and loans or readjusting their operations to reach customers online. Some are now offering curbside service and deliveries or are benefiting from residents who buy local to keep cherished Winchester businesses from going under.

When the pandemic struck in early spring, the American economy fell into a sickening freefall as businesses everywhere shuttered and consumers stayed home to avoid infection. The economy's gross domestic product, the broadest measure of output, plummeted at a 31.4% annual pace from April through June. It was, by far, the worst three months on record dating to 1947.

Even though hiring partly rebounded as businesses began to reopen, the nation is still down 10.7 million jobs since February.

Lacking the credit access and cash stockpiles of larger companies, small businesses were especially vulnerable to the economy’s sudden stop. In a study in April, researchers from the University of Illinois, the University of Chicago and Harvard found that three-quarters of small businesses had only enough cash on hand to get by for two months.

Many crumpled under the pressure. Yelp, which publishes reviews of restaurants, bars and other businesses online, reports that nearly 164,000 businesses on its website have closed since March 1 — 98,000 of them permanently.

Extrapolating from numbers provided by Yelp and Womply, Steven Hamilton, an economist at George Washington University, estimates that 420,000 U.S. small businesses had closed permanently by July 10.

And small businesses’ troubles aren't confined to their stressed-out owners. They generate nearly 44% of U.S. economic output, according to the Small Business Administration, and account for two-thirds of new hiring. (The SBA generally defines small businesses as those that employ no more than 500 workers.)

In addition to their economic impact, small businesses define communities.

“Let’s talk about the tapestry of people and communities,’’ said Andre Dua, a senior partner at the McKinsey consultancy, who has studied COVID-19’s impact on small businesses. “What is New York without its restaurants?’’

Or Brooklyn without its boutiques?

Diana Kane opened her clothing and jewelry shop on Brooklyn’s Fifth Avenue in 2002, years before that New York City borough was hip.

“The rents were inexpensive," she said. "The street was quiet and a little sketchy.’’

But the timing was right: “Fifth Avenue grew up around me.’’

Suddenly, the neighborhood was bustling with shops, restaurants and bars. Then the pandemic struck, hitting New York hardest of all.

“We were the epicenter of the outbreak,” Kane said. “There were sirens literally nonstop. Everything was closed. We were in the depths of it.’’

And it all happened during her busy spring season. Her clothing sales evaporated — down 78% in April. She couldn’t persuade her landlord to agree to a rent reduction.

So she closed the Diana Kane Boutique in May.

Kane regrets the impact that her decision had on her customers, suppliers and neighbors.

“There are repercussions all the way down the supply chain,’’ she said. “My money circulates in the community. . . The money I made went to pay for baseball, restaurants, bookstores, dry cleaning. It’s devastating.’’

Across the country in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Leslie Moody is fighting to hold on to Rancho Gallina, the boutique hotel she opened in 2013 with her husband. In January, they were looking forward to a banner year -- forecasting $20,000 a month in revenue from room bookings and weddings and other events.

“By the end of April, everything had cancelled or postponed,’’ Moody said.

The rescue aid program the federal government enacted in March helped them survive. In addition to their state jobless aid, she and her husband could each collect $600 a week in federal unemployment benefits — until that program expired July 31.

“That was the money that meant we didn’t have to hold our breath every month,” Moody said. “Now we’re in breath-holding mode.’’

She, too, worries about how closing down would, in turn, hurt others.

“We bring a lot of income into the area,’’ she said. “For instance, there’s this really creative food truck company that caters all our weddings.’’

And they buy produce from local farmers.

“It does trickle out, even though we’re a small business.’’

Governments at all levels did scramble to protect small businesses. In addition to the expanded unemployment aid, Congress approved the Paycheck Protection Program, which provided $520 billion for 5 million businesses, most of them small.

In Winchester, too, the city government offered small grants — Christine Patrick’s Winchester Book Gallery received $500 — and suspended parking fees to encourage shoppers to keep visiting the downtown pedestrian mall.

But Congress has failed to agree on another financial rescue. Without further federal aid — soon— economists warn that the recovery will likely falter and intensify pressure on small businesses that are straining to survive.

“If we have to wait until January, an extremely large number of small businesses will fail," Hamilton, the George Washington University economist, said at a Brookings Institution conference last month. “In the hundreds of thousands ... We can’t last until January. That would be catastrophic.’’

To hang on, many small businesses have tried to reinvent the way they do business.

“Change comes from desperate firms trying new things,’’ said Giuseppe Gramigna, a small business consultant and former chief economist at the SBA.

The flexibility may be paying off for some.

Businesses with fewer than 500 employees were hurt the most when the pandemic struck: They slashed 16.4% of their jobs between February and April, versus a 14.1% drop in employment at companies with 500 or more workers, according to ADP. But since April, employment at the smaller businesses has rebounded somewhat faster than at larger companies.

In Winchester, Emily Rhodes, owner of Polka Dot Pot, didn’t wait. She knew that the pandemic, and the lockdowns it would require, could wreck her business of offering pottery-making classes. Working with a tech-savvy friend in Ohio, she and her staff created a website from scratch, started taking orders and arranged for curbside pickup.

“To-go kept us going,’’ she said.

Rhodes also started delivering craft kits to customers. She dressed up as the Easter Bunny to take packages to children in April.

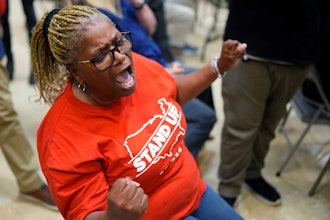

At the Hideaway Café, owner Victoria Kidd took a similar approach. The Hideaway began delivering “quarantine care packages.’’ Adults would receive wine or beer, baked goods, a roll of toilet paper and a thank you note from Kidd’s 7-year-old daughter. Children would receive sweets, delivered by café staff in costumes — a pirate, a wizard, a unicorn or Star Wars’ Kylo Ren.

Kidd also had another idea: “Beverage bonds’’ that allowed customers to pay now for coffee they’d drink later. The drive generated $10,000. As it turned out, few of the buyers ever redeemed their bonds; they just wanted to keep the café going.

The threat to their small businesses, it seems, evoked a protective instinct in Winchester residents. Many shared the idea, said Christine Patrick of the Book Gallery, that “If Amazon and Google own the world, we’re in trouble.’’

Despite those efforts, Hamilton at George Washington University fears the damage will be long-lasting.

“It is much easier to close a business than to start one,'' he said. After the Great Recession, “it took more than a decade to get back to the number of small businesses we had in 2008."

He expects business losses this time to double the number that shuttered in the Great Recession.

“It seems clear to me that the COVID-19 crisis is going to have an extremely deep scarring effect on the small business sector," Hamilton said, "and through it the American job market and economy."