High-stakes climate talks outside Paris are dragging into an extra day as diplomats try to overcome disagreements over how — or even whether — to share the costs of fighting climate change and shift to clean energy on a global scale.

Negotiators from more than 190 countries are aiming at something that's never been done: agreeing for all countries to reduce man-made carbon emissions and cooperating to adapt to rising seas and increasingly extreme weather caused by human activity.

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said Friday that negotiators are still in disagreement over how far-reaching the accord should be and who should pay for damages wrought by global warming.

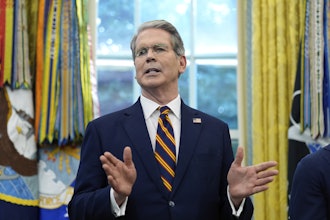

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry zipped in and out of meetings on his fifth straight day in France trying to iron out differences with developing countries such as India. Kerry said he's "hopeful" for an accord and has been working behind the scenes to reach compromises.

"There was a lot of progress made last night, a long night, but still a couple of very difficult issues that we're working on," Kerry told reporters Friday at the talks outside Paris. He wouldn't elaborate on which issues.

The talks had been scheduled to wrap up Friday. But after tense overnight negotiations, French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius postponed and said he is aiming to have a final draft Saturday morning that could be adopted by Saturday afternoon.

"We are almost at the end of the road," Fabius said.

"There are still outstanding issues," Ban told reporters Friday in Le Bourget, outside Paris. Among them are "ambitions, climate financing" and so-called differentiation — whether big emerging economies like China and India should pitch in to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and help the poorest countries cope with climate change.

Ban said he's "convinced and confident" that negotiators will reach an "ambitious, strong accord."

The two-week talks are the culmination of years of U.N.-led efforts for a long-term climate deal. U.N. climate conferences often run past deadline, given the complexity and sensitivity of each word in an international agreement, and the consequences for national economies.

Analysts said the delay is not necessarily a bad sign.

"This needs consensus," said Michael Jacobs, an economist with the New Climate Economy project, speaking to reporters outside Paris. "There's a lot of negotiating to do."

Sam Barratt of advocacy group Avaaz, added: "We would rather they take their time and were patient with the right deal than rush it and get a breakdown. ... Getting 200 countries to agree on anything is tough. Getting them to agree on the future of the planet and a deal on climate change is probably one of the toughest pieces of negotiation they'll ever get involved in."

Some delegates said a new draft accord presented late Thursday by Fabius allowed rich nations to shift the responsibility to the developing world.

"We are going backwards," said Gurdial Singh Nijar of Malaysia, the head of a bloc of hardline countries that also includes India, China and Saudi Arabia.

They have put up the fiercest resistance against attempts by the U.S., the European Union and other wealthy nations to make emerging economies pitch in to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and help the poorest countries cope with climate change. The issue, known as "differentiation" in United Nations climate lingo, was expected to be one of the last to be resolved.

Nijar said it was unreasonable to expect countries like Malaysia to rapidly shift from fossil fuels — the biggest source of man-made greenhouse gas emissions — to cleaner sources of energy.

"We cannot just switch overnight ... and go to renewables," he said, on a coffee break between meetings at 1:30 a.m. "If you remove differentiation you create very serious problems for developing countries."

This accord is the first time all countries are expected to pitch in — the previous emissions treaty, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, only included rich countries.

The latest, 27-page draft said governments would aim to peak the emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases "as soon as possible" and strive to reach "emissions neutrality" by the second half of the century.

That was weaker language than in previous drafts that included more specific emissions cuts and timeframes.

The biggest challenge is to define the responsibilities of wealthy nations, which have polluted the most historically, and developing economies including China and India where emissions are growing the fastest.

The draft didn't resolve how to deal with demands from vulnerable countries to deal with unavoidable damage from rising seas and other climate impacts. One option said such "loss and damage" would be addressed in a way that doesn't involve liability and compensation — a U.S. demand.